I’m a big fan of Bruce Campbell, I can’t deny it. He has a great screen presence. He’s no Laurence Olivier but he’s just so much fun to watch. My rationale for liking him so much comes from, unsurprisingly, his most memorable role, that of Ash from “Evil Dead.” So many horror movies take themselves too seriously, they try to blow you away with gore, with suspense, with sheer jump-out-of-your-seat moments, or just how scary they can be. Bruce Campbell in “Evil Dead” always made me feel like it was scary and it was a horror movie but that at no point was there any real danger. Like somehow, consciously or unconsciously, he had the interests of his audience at heart. And even though he was only a playing character trying to save humanity from the forces of darkness, somehow, he was actually doing that too by subtly giving the proverbial wink and nod to everyone watching the film, reminding us not to get lost in the Hollywood shuffle. Intentions aside, Bruce Campbell is funny and he’s a leading man if there ever was one. Almost a caricature of a leading man, but a leading man nevertheless.

In 1997’s “Running Time,” one can see Campbell in good form. He delivers his characteristic tough guy demeanor and his no-nonsense approach to on-screen, in-character business. But Bruce Campbell isn’t the only thing about “Running Time” that makes it great.

Like Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rope,” the movie is intended to have the appearance of being cut-free, in other words, devoid of cuts from shot to shot. Most movies have hundreds of cuts. And although one can not (or perhaps could not because technologies have changed a lot over the last 30 years) truly make a cut-free movie (because rolls of film only translate to around 10 minutes of film time, at which point, you need to stop and reload the camera), this one was about as cut-free as they come, having around 30 in total which are hidden throughout the film. This style works very well with the subject matter of the film (a heist) where time is a crucial component of success. That was not an accident as you might expect. Becker, the director, intentionally created a script about a heist in order to use this technique of a cut-free movie. And, in case you are wondering, the idea for the style preceded the script and not the other way around.

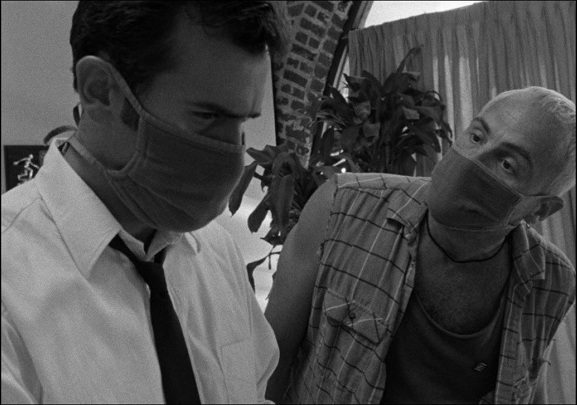

Having read through some history of the film from the director’s point of view, I can tell you that there are many more interesting things about this movie than just its shooting style, its resemblance to a play, Bruce Campbell, or the eerie prescience of the actors wearing surgical masks during the heist itself (hint: think recent worldwide health crisis). For instance, the movie is shot on 16mm ASA 64 Kodak black and white film. 64 ASA film is incredibly slow meaning getting the exposure right is very difficult. However, the image you end up with if you have exposed it well is very, very sharp and very very low grained. For comparison, Clerks was shot on something called Kodak Eastman Double-X which (if I have understood it correctly) has an ASA of around 200 indoors and 250 outdoors (though I don’t know why a film should be rated differently between indoors and outdoors). That’s like 4 times as fast as the film stock used to make “Running Time” and, if you hearken back to an image of Clerks, you will perceive how grainy it was and how sharp this is.

The movie definitely seems like a play, especially in the interactions between Campbell and Barone. The long take(s) just make it seem less like we (the audience) are seeing the characters on a screen and more like they are performing right in front of us. Barone’s acting is not stellar and neither is Campbell’s but that’s not why you go to see a Bruce Campbell movie as anyone who has seen one can probably tell you. You go to see a Bruce Campbell movie because he kicks ass, it’s kind of that simple. That said, the dynamic between Barone and Campbell is compelling, he with his Ex-con mannerisms and she with her down-on-her-luck-resorting-to-prostitution-to-pay-the-bills persona. It’s not high art by any means but their relationship is moving in a way. The idea that two wayward people can somehow come together to rescue each other from their own foibles is something I’ve always wanted to believe in and it’s a pleasure to see it on-screen in the form of this movie.

It’s not a perfect film mind you, it does have some problems. A lot of the camera work I think could have been better, there were many times when the focus was a bit off. But the nature of the movie pretty much assured that getting a perfect shot was never going to happen. Maybe you could get the focus just right if you had a hundred takes to do it but that couldn’t be done here. I also thought, when you come right down to it, there just wasn’t quite enough plot to really make a movie here. The heist itself isn’t quite enough and neither is the long lost romance between Barone and Campbell. The heist is great movie fodder but the more cleverly it is executed on-screen, the greater the pleasure of watching it take place and the less you need other plot points to make the movie sing. I recognize that the idea of the movie was that things were going wrong and the emphasis was on the psychological impact this had on the characters but heist movies do need energy and I thought this was a bit low on that. Take for comparison, the heist scene at the beginning of “Snatch,” by Guy Ritchie. There is a very slow build up of the characters entering the building and traveling to the appropriate floor via elevator and then just a few seconds of high intensity action as the heist is carried out. This sort of “smash and grab” film-making really shoots through your veins and a heist, in my opinion, must be shot in such a way that the audience experiences this rush.

Running Time, in short, is a lot of fun. It’s an innovative concept for a movie and for the most part, everything about it works really well. One of the biggest drawbacks to the medium of film is that it removes the audience from the action much more than a play does and this film, in some strange way, attempts to reconcile this. And, for the most part, it succeeds.